Safety matches.

The first safety matches, ignited by friction against a specially prepared surface, were created in 1845 in Sweden, where their industrial production began in 1855 by J. Lundström. This became possible thanks to the discovery of non-toxic amorphous phosphorus by A. Schrotter (Austria) in 1844. The head of the safety matches did not contain all the substances necessary for ignition: amorphous (red) phosphorus was deposited on the wall of the matchbox. Therefore, the match could not light accidentally. The composition of the head included potassium chlorate mixed with glue, gum arabic, crushed glass and manganese dioxide. Almost all matches made in Europe and Japan are of this type.

Kitchen matches.

Matches with a double-layer head, lit on any hard surface, were patented by F. Farnham in 1888, but their industrial production began only in 1905. The head of such matches consisted of potassium chlorate, glue, rosin, pure gypsum, white and colored pigments and a small amount phosphorus. The layer at the tip of the head, which was applied with a second dipping, contained phosphorus, glue, flint, gypsum, zinc oxide and coloring matter. The matches were lit silently, and the possibility of the burning head flying off was completely excluded.

Match books.

Cardboard matchbooks are an American invention. The patent for them, issued to J. Pussey in 1892, was acquired in 1894. At first, such matches did not receive public recognition. But after one of the beer manufacturing companies purchased 10 million match books to advertise its products, the production of cardboard matches became big business. Nowadays, matchbooks are distributed free of charge to gain the favor of customers in hotels, restaurants, and tobacco stores. There are twenty matches in a standard book, but books of other sizes are also available. They are usually sold in packs of 50. Booklets of special design can be supplied in packages of various sizes, most suitable for the customer. These matches are the safety type, the surface for their ignition is the bottom (covered with “grey”) flap of the cover, under which the front side is tucked.

Long, as large and other types are called

The length of standard hunting matches is about 40-50 mm . But there are also large products on sale , the length of which reaches 85 mm. Large matches do not have a separate name; the difference is the size of the coating, which covers only half of the rod. While products of standard sizes are almost completely covered with an incendiary mixture. Hunting matches are packaged in cardboard boxes and plastic blisters. The second type of packaging is more preferable, as it increases the protection of products from harmful influences. The number of matches in a cardboard box is most often 20 pieces, in a blister - 6. Hunting matches differ according to the brand, color of the head and coating.

HeimHelfer Hunting matches in blister pack. Photo by OZON

Impregnation of matches.

Until 1870, fire-prevention impregnation methods were not known to prevent flameless burning of the remaining coal on an extinguished match. In 1870, the Englishman Howes received a patent for the impregnation of matches with a square cross-section. It listed a number of materials (including alum, sodium tungstate and silicate, ammonium borate and zinc sulfate) suitable for impregnating square matches by immersing them in a chemical bath.

Impregnation of round matches on a continuous match machine was considered impossible. Due to the fact that the legislation of some states since 1910 required mandatory fire impregnation, employee W. Fairbairn in 1915 proposed, as an additional operation on a match machine, immersing matches approximately 2/3 of the length in a weak solution (approx. 0.5%) of phosphate ammonium

Criterias of choice

When choosing hunting matches, it is recommended to take into account several standard criteria: cost, brand (manufacturer), length of products, number of pieces in the package. It is recommended to buy matches in sealed packaging , which provides protection from external influences. It is first necessary to check the quality of hunting matches: do they burn under water and after getting wet? Do they light up in strong winds? It is important to remember that there are a large number of low-quality products on sale, so it is recommended to purchase matches from trusted suppliers or directly from manufacturers.

Hunting matches Survival 43 mm. (does not go out in water). Photo by OZON

Phosphorus sesquisulfide.

White phosphorus, used to make matches, caused bone disease, tooth loss, and necrosis of jaw areas among match factory workers. In 1906, an international agreement was signed in Bern (Switzerland) prohibiting the manufacture, import and sale of matches containing white phosphorus. In response to this ban, harmless matches containing amorphous (red) phosphorus were developed in Europe. Phosphorus sesquisulfide was first obtained in 1864 by the Frenchman J. Lemoine, mixing four parts of phosphorus with three parts of sulfur without access to air. In such a mixture, the toxic properties of white phosphorus did not appear. In 1898, French chemists A. Seren and E. Cahen proposed a method of using phosphorus sesquisulfide in match production, which was soon adopted in some European countries.

In 1900 she acquired the right to use a patent for matches with phosphorus sesquisulfide. But the patent claims were intended for matches with a simple head. The quality of sesquisulfide matches with a two-layer head turned out to be unsatisfactory.

In December 1910, W. Fairbairn developed a new formula for harmless matches with phosphorus sesquisulfide. The company published the patent claim and allowed all competitors to use it for free. A law was passed placing a two-cent tax on every box of white phosphorus matches, and white phosphorus matches were forced out of the market.

Accidental discovery

In 1827, the English chemist and apothecary John Walker discovered that if you coat the end of a wooden stick with a certain chemical composition, then when it is rubbed against a dry surface, the head lights up and sets the stick on fire. Among the chemicals he used, antimony sulfide, bertholite salt, gum and starch. And it all happened by chance. John mixed the chemicals with a stick. A dried drop formed at the end of this stick. To remove it, he struck the floor with a stick. And suddenly a fire broke out! Walker did not bother to patent his invention, but showed it to everyone. A certain Samuel Jones, who was present, quickly realized the value of the pharmacist’s find. Soon he began making and selling incendiary sticks, calling them “Lucifers.” However, his products also had disadvantages: they smelled bad and, when ignited, scattered clouds of sparks around. Nevertheless, the first sale of matches took place on April 7, 1827 in the city of Hikso. There was another problem - the head of the first matches consisted of only phosphorus, which ignited perfectly, but burned out so quickly that sometimes the wooden stick did not have time to ignite. We decided to return to the old recipe - a sulfur head and began to apply phosphorus to it to make it easier to set fire to the sulfur, which in turn set fire to the wood. Soon they came up with another improvement to the match head - they began to mix chemicals with phosphorus that, when heated, release oxygen, which promotes better combustion. In 1832, so-called dry matches appeared in Vienna - the invention of Trevani, who began to apply a mixture of Berthollet salt with sulfur and glue to the head of a wooden straw. If you struck such a match on sandpaper, the head instantly ignited. Unfortunately, sometimes this was accompanied by a slight explosion, which caused the hands (well, if not the eyes) of the person striking. The ways for further improvement of matches were predictable: it was necessary to make such a composition of the mixture that it would light up quietly. The problem was solved by using a new composition based on berthollet salt, white phosphorus and glue. Matches with such a coating easily ignited when rubbed against any hard surface - glass, leather or a piece of wood. The inventor of the first phosphorus matches was 19-year-old Frenchman Charles Soria. In 1831, a young experimenter added white phosphorus to a mixture of Berthollet salt and sulfur to weaken its explosive properties. A year later, this recipe was recreated by the German chemist Jacob Kammerer. But the low ignition temperature of the new matches was fraught with fires. In addition, white phosphorus turned out to be very poisonous. Match factory workers suffered seriously from its fumes. In 1833, a matchbox with rough paper glued to it was born. Now there was no longer any need to strike a match against anything, but there was still a danger that sometimes the phosphorus matches in the box would spontaneously ignite as a result of friction. In this regard, the search began for a safer flammable substance. In 1847, Schröter discovered red phosphorus, which was no longer poisonous. The first combustible mixture based on it was created by the German chemist Betcher. He made a match head using glue mixed with sulfur and bertholet salt, and impregnated the match wood with paraffin. This match burned great, but its only drawback was that it did not ignite, as before, when rubbed against a rough surface. Boettcher solved the problem by applying a composition containing red phosphorus to the surface of the head. Now the matches burned with an even yellow flame, without smoke or unpleasant odor.

Production of wooden matches.

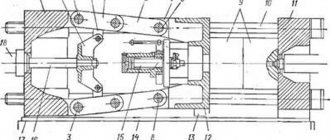

Modern wooden matches are made in two ways. With the veneer method (for matches with a square cross-section), selected aspen logs are sanded and then cut into short logs, which are peeled or planed into strips corresponding in width to the length of the matches, one match thick. The ribbons are fed into a match machine, which cuts them into individual matches. The latter are mechanically inserted into the perforations of the plates of the machine for applying heads by dipping. In another method (for round matches), small pine blocks are fed into the head of the machine, where die-cutting dies arranged in a row cut out the match blanks and push them into the perforations of metal plates on an endless chain.

In both production methods, matches pass sequentially through five baths in which a general impregnation with a fire-fighting solution is carried out, a ground layer of paraffin is applied to one end of the match to ignite the wood from the match head, a layer forming the head is applied on top of it, a second layer is applied to the tip of the head and then Finally, the head is sprayed with a strengthening solution that protects it from atmospheric influences. After passing on an endless chain through huge drying drums for 60 minutes, the finished matches are pushed out of the plates and enter a filling machine that distributes them into matchboxes. The wrapper then wraps three, six, or ten boxes in paper, and the packaging machine fills them into shipping containers. A modern match machine (18 m long and 7.5 m high) produces up to 10 million matches in an 8-hour shift.

Subtleties of business

To all of the above, we can add that there are about a hundred different types of matches. They are distinguished by the degree of combustion, composition, color and size.

When expanding the production of matches, it is necessary to improve the technological process. The success of this business depends on this. You should also learn new types of matches.

Eg:

- Hunting. They differ from ordinary ones in that, in addition to the stick and head, they have additional coating. Thanks to this, the match burns for a long time with a large flame. They light up fairly easily in any weather. Compared to a regular match, a hunting match burns much longer.

- Storm. This species does not have a head, but the main part has much thicker coating (compared to hunting ones). Their ignition ability is very high due to the fact that the incendiary mass contains a lot of berthollet salt. These matches can light up in any weather (even in a force twelve storm). They are mainly used by fishermen and sailors.

- Gas or fireplace. Their length is much longer (compared to ordinary matches). Their main purpose is to light the burners of gas stoves or fireplaces.

There are also thermal matches. They are capable of generating such amounts of heat that they can even be used for soldering. Signal matches are no less unique. They burn with multi-colored flames. There are also photographic matches. They are used to create an instant flash. There are also souvenir and gift items available. In general, when organizing the production of matches, the variety of goods is selected on an individual basis.

Production of cardboard matches.

Cardboard matches are made on similar machines, but in two separate operations. Pre-treated cardboard from large rolls is fed into a machine that cuts it into “combs” of 60–100 matches and inserts them into the nests of an endless chain. The chain carries them through the paraffin bath and the head forming bath. The finished combs go into another machine, which cuts them into double “pages” of 10 matches and seals them with a pre-printed lid equipped with a strike strip. The finished matchbooks are sent to the filling and packaging machine.